Issue 9: Key findings from the community-based participatory research on FGM

30th of June 2015

Perception about the consequences of FGM among migrant communities in the EU

One of the often mentioned reasons for the continuation of FGM among migrants is the lack of knowledge about the adverse consequences of the practice. Our research revealed that although individuals' perception about the negative consequences of FGM could influence them to abandon the practice, many members of the affected communities had poor knowledge about such consequences and were less persuaded to stop the practice.

Across the communities it was commonly perceived that the use of un-sanitised tools to perform FGM pose significant health risks, including infection. Many people also expressed concern about the physical pain associated with the non-use of anaesthetics in most FGM procedures. Even most of those who supported FGM also held these beliefs, and often recommended medicalization rather than the eradication of the practice. However, a few women believed that the physical pains of FGM procedure are essential because they enable girls to be able to withstand the difficulties of life.

"People talk about the pain, but it is good for our girls. Life is full of difficulties, especially childbirth. If you can withstand the pain of FGM then there is nothing you cannot withstand in life." (Female participant, Guinea Bissauan community, Lisbon)

There was also a mention of FGM being associated with obstetric complications, including painful labour, caesarean section, haemorrhage as well as menstrual pains and fistula. Some respondents also perceived that FGM is related to poor sexual wellbeing, including painful sex and low sex drive.

"A lot of women [who have undergone FGM] have problems with their husbands. They are scared when it is time for bed. The men think their wives don't love them, but the problem is because of FGM, sex is painful for the women." (Female participant, Senegalese/Gambian community, Banyoles)

However, a number of participants in the Guinea Bissau community were dismissive of the fact that FGM affects the reproductive health of women, mostly citing their ability to have children despite having being cut as a reason for the scepticism. A number of respondents also believed that only infibulation is harmful, and that clitoridectomy and excision, which are the types they practiced, are not.

"What they are saying about FGM is not true. All of us here have done it but none of us encountered any problems conceiving. I have eight children and I'm still alive, no operation. So it is a lie" (Female participant, Senegal/Gambian community, Spain)

Interestingly, respondents rarely talked about the psychological effects of FGM. Some key informants explained this to be partly due to the communities' lack of appropriate local terminologies for describing psychological conditions. Nonetheless, a few women reported that flashbacks of their FGM procedures as well as the mention of 'mutilation' or 'FGM' are traumatising.

"The experience I have passed through is not a joke. I still recollect that pain, the blood I lost, the moment I wanted to pee but couldn't. That is what comes to mind when I hear people talk about FGM, it is not a comfortable feeling." (Female participant, Guinea Bissauan community, Lisbon)

Owing to the strong religious faith of the migrants, most illnesses were perceived to be spiritually rooted, including those that are potentially caused by FGM. Many people believed that they will receive divine protection against the negative effects of FGM because they did it for God. Some others were also of the view that the fact that Prophet Mohammed and their ancestors sanctioned FGM is a proof that it is not harmful.

"We do it [FGM] because of God. It is part of our religion.. God will protect us from all the bad things associated with it." (Male participant, Guinea Bissauan community, Lisbon)

These findings suggest the need for more education on the adverse health effects of FGM in the affected communities. People who had good knowledge about the effects of the practice were mostly strongly against it, suggesting that education on the adverse health consequence could persuade people to abandon it. Such education needs to be rooted in practical evidence of actual adverse health impact of FGM in order to be more effective.

As part of the REPLACE 2 project, community-based participatory research was conducted to understand the nature of FGM among three affected communities in the EU. These include the Eritrean/Ethiopian community in Italy, the Guinea Bissauan community in Portugal and the Senegalese/Gambian community in Spain. This edition of the newsletter presents short articles on some of the key findings from this research.

Decision-makers on FGM in migrant communities in the EU

Our research discovered several key actors at the household and community levels who influence the continuation of FGM in the study communities. FGM was generally practiced on young girls; with decisions on the practice made by a third party without the consent of the girl being sought.

At the household level, parents were reported to be most influential over the daughters' FGM decision. Owing to the patriarchal nature of households in the communities, women (wives) were primarily responsible for instigating and facilitating the process for the girl to be subjected to FGM. Although FGM was largely perceived as a women's issue, men (husband) were the ultimate decision-makers over their daughters' FGM due to their role as financiers:

"The women are the ones who push for it [FGM], and then the men accept and pay for it. Men are the boss.. The wife needs the consent of her husband before she can send the girl to FGM." (Female participant, Guinea Bissau community, Lisbon)

Paternal grandmothers were reported to be very influential on FGM as well. They perceived themselves as cultural custodians, and enforced FGM either by directly subjecting the girl to it or applying pressure on the girl's parents. Although most grandparents live in the home country, they still exerted greater influence through regular telephone communication with the girl's parents. Grandparents were particularly influential because they were regarded as an embodiment of wisdom and with sacred powers that could be evoked to cause harm on those who disrespect them.

"It is the grandmothers who promote it [FGM]. Sometimes parents don't want to cut their daughters... My father never wanted us to be cut but my grandmother persisted a lot and I got cut." (Female participant, Guinea Bissauan community, Lisbon)

Many women expressed enormous pressure from their mothers-in-law and said they often felt obliged to adhere to their decisions due to fear of marital conflict and the perception that girl belongs to the father's family.

"My mother-in-law insisted that my daughter should be circumcised. I couldn't stop it because she is their grandmother. And if they want her to do it who am I to say no? (Female participant, Senegal/Gambia community in Banyoles, Spain)

At the community level elderly women were generally proactive in promoting FGM. They also instigated and persuaded parents to subject their girls to the practice, and perceived their role as a way of honouring the ancestors. Also, they feared that they would be punished by the ancestors if they failed to protect the cultural practices and they become extinct. Other influential actors at the community level included excisors and religious leaders. Although excisors were not very common in the study communities, they were thought to be very influential in the home country when parents visited with the girl. They were also respected and feared, and believed to possess mystical powers that could bring misfortunes to people who disobeyed them. Most religious leaders in the communities did not often publicly support FGM, even though they were reported to be very influential in the home countries when parents visited. Many members of the communities perceived religious leaders as a credible source of knowledge, suggesting that they are very influential on FGM.

These findings thus underscore the need to engage with parents, religious leaders and community elders in intervention work on ending FGM. The influence of actors in the migrants' home country also suggests the need to tackle FGM in the home countries if greater strides are to be made in ending it in Europe.

Migrants' access to FGM related health and social services

The ability of FGM survivors to access specialised FGM services is imperative, especially given the adverse health consequence of the practice. Yet our research discovered poor awareness of FGM services across all the affected communities. Nearly all the participants said they were unaware of any specialised FGM services or organisation in their community. This was partly due to lack of information and supply of FGM related services. In Portugal, Italy and Spain, where the research was conducted, FGM was treated as a general health and social issue without specialised services set up for it. Most participants did not generally know where to seek help if they had problem with FGM.

"Here in Palermo, I've never heard of anything for people who have FGM problems. If you have a problem you don't know where to go. Maybe you have to go to the hospital, but I don't." (Female participant, Eritrean/Ethiopian community, Palermo)

Also, most women were ignorant about treatment that FGM survivors could have to improve their condition. When asked about their views on reconstructive surgery, the majority of survivors said they had never heard of it. Those who understood the procedure after it was explained to them said they did not want it because it "will not make much difference to their condition."

"Actually I didn't know about it [reconstructive surgery]. But even if they did it, the feeling will still be the same. Why do the surgery? It is already done. it is our culture and every woman should do it." (Female participant, Guinea Bissauan community, Lisbon)

Many women expressed their anxiety towards going to the hospital with an FGM problem. Also, they lacked confidence in the ability of health workers to deal with FGM related health problems. Health workers were thought to be ignorant about FGM, and often disoriented when presented with an FGM related problem. Some survivors said they felt embarrassed when health workers expressed surprised at their FGM.

Participants also expressed a lack of trust in social services and the police to deal with FGM issues. As a result, they rarely sought help from social workers or the police when they were confronted with an FGM issue. Social service workers were generally perceived to be "intrusive", "patronising" and "insensitive". Although participants mostly attributed their poor relationship with these agencies to their African identity, it appeared part of the problem was due to language barriers and a lack of interpreters to mediate conversations between the migrants and the professionals.

When participant were asked about the sort of support they needed in relation to FGM, most of their suggestions were surprisingly not health-related. Those who supported the practice mostly recommended the legalisation and medicalization of the practice. Participants who were against the practice suggested the need for more public education about the harmful effects of FGM and the prosecution of perpetrators.

These findings underscore the need for government and civil society organisations to establish specialised services for FGM survivors and also raise awareness about available services. Equally, it is imperative to educate health and social service professionals about FGM so that they are better able to deal with it. Also, there is a need to build trust between health workers, social workers and the police on the one hand and FGM affected communities on the other.

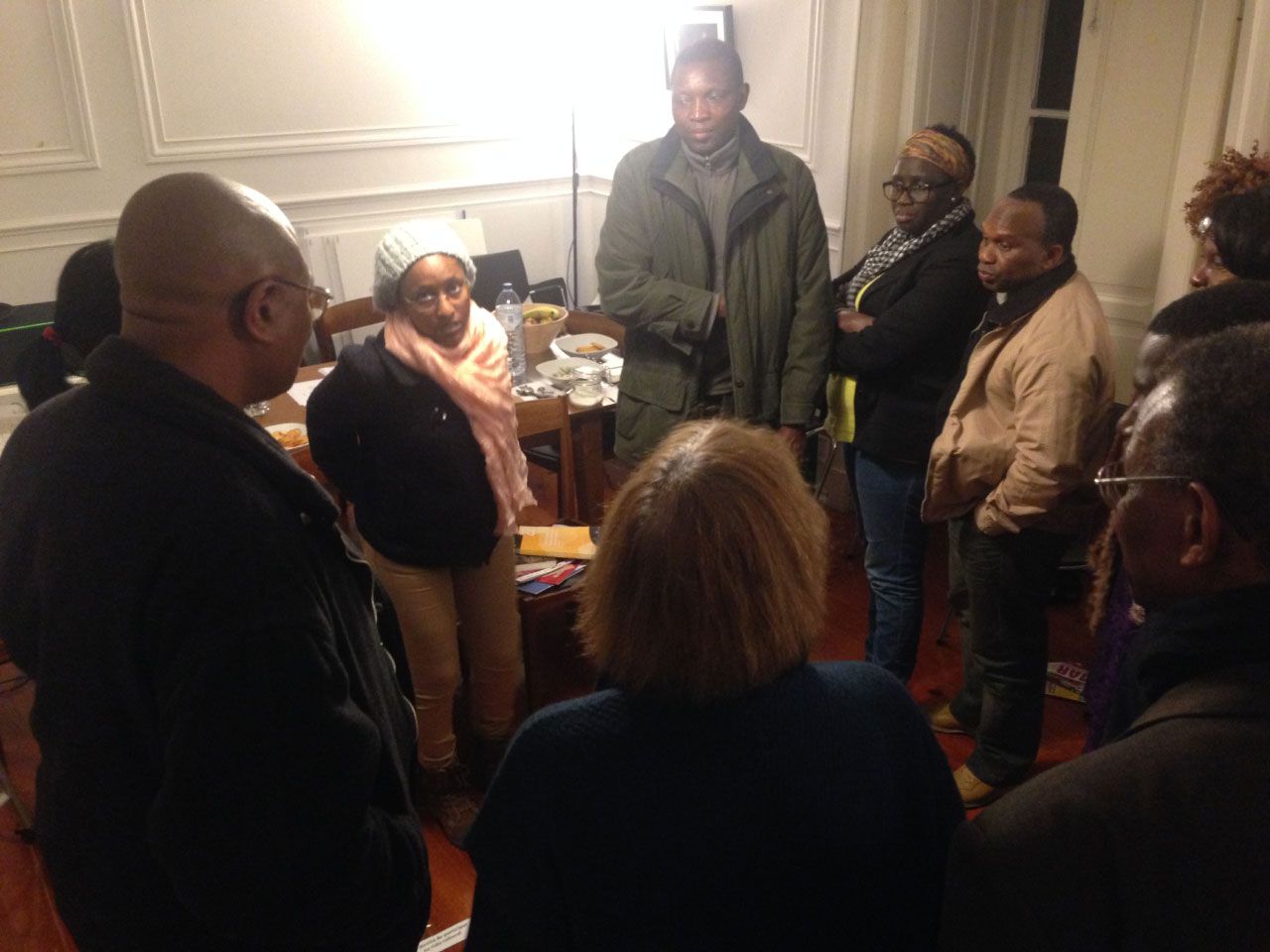

After the community-based participatory research, community members have been involved in intervention workshops in all cities. In the picture, APF workshops with Guinea Bissauan community in Lisbon (Portugal).REPLACE 2 is followed by more than 500 stakeholders! Help us disseminate our work by spreading the word through our website and social network pages:

https://twitter.com/replacefgm2

If you need any advice from the REPLACE 2 team please write to:

To unsubscribe to this email please click here or to contact us visit our website at www.REPLACEFGM2.eu info@REPLACEFGM2.eu

(REPLACE 2 Project Number:

JUST/2011-2012/DAP/AG)

The sole responsibility for the content of

this leaflet lies with the authors and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the

European Commission.

The European Commission is not responsible for

any use that may be made of the information

contained therein.