|

|

Issue 7: Community engagement and Female Genital Mutilation behaviour change: experiences in UK and The Netherlands 5th of December 2014 Sharing insights on community women's behaviour change intervention in London Focus groups were conducted by Foundation for Women's Health Research and Development (FORWARD) in December 2013 with 21 women from Somalia and Sudanese communities to assess their readiness to work on FGM based on an adapted version of the Community Readiness Assessment Interview Questions (Plested et al., 2006). Following on from the assessment, women were recruited from the two communities to take part in the community workshops. This also included some of the women who had previously taken part in the focus groups discussion. Through a mix of snowballing techniques and adverts in local shops 25 women were recruited to take part in the training. The community workshops ran from March to May 2014 and targeted 25 women all residents in West London. The four hour workshops consisted of eight sessions of FORWARD's women's health and leadership training course which aims to provide women with leadership skills, information and knowledge on FGM and related issues. It also provided an opportunity to identify the behaviours that women will address in their community intervention activities which was scheduled after the workshops. The women's health and leadership course included the following:

The course provided a foundation for the women to begin their FGM outreach work within their communities. The majority of the women had indicated that they wanted to have more confidence to speak about FGM and specifically tackle the community views that FGM is not a problem and some types of FGM are okay as they are required by religion. The women have set up a WhatsApp Group to communicate with each other about their community activities and meet monthly at FORWARD to share their experiences. The women will start to implement specific behaviour change activities in their communities from January to March 2015. Changing behaviour in the Netherlands: FGM is not required by religion In the Netherlands, REPLACE 2 was introduced within several organisations from the Somali community in Rotterdam & surrounding areas. Through this meetings 13 women were invited to be trained as community facilitators on women health, FGM and leadership. Looking at behaviour and what could be changed is a process, a focus group discussion has been carried out by REPLACE 2 team in The Netherlands to look what possible behaviour can be targeted for a new intervention. The first meeting started with an introduction about the history of the first REPLACE project and the focus of REPLACE 2. Afterwards, they conducted 6 days training for 3 hours. The training contents were the following subjects:

Points of discussion were mainly focused on how to stop all forms of FGM. In the Netherlands it is publicly known that there are some parents who are eager to circumcise their daughters in the lightest form of FGM (some called this type sunna ). The reason is that they believe the lightest form of FGM is a sunna, which has religious meaning. The word sunna is something good or nice to do as reward of being a good believer. The question was how to change this behaviour: this could be done through the empowerment of youth and their parents. Make them aware of the fact that FGM does not have a religious basis, but it is indeed solely a cultural practice. The target behaviour identified to change is religious leaders teaching that FGM is not required by Islam. This involved finding religious leaders (imams, Koran Tutors, etc) who were open to a discussion about the idea, wiling to accept the information, and training and who dare to speak up about religion and FGM. The training facilitated the increase in awareness and knowledge, as well as empowering and equipping them with the skills to speak out. One of the assignments given during the training for community women was to visit the Koran tutors of their own children and ask questions about FGM. The outcome was surprisingly positive, both male and female tutors, were willing to teach against FGM. The 13 women trained as community facilitators on women health, FGM and leadership carry the responsibility to support the Koran tutors in order to share information and knowledge within their community. |

|

|

|

"I went to Sudan in September to meet my family after 5 years being away and took the chance to find out more about FGM in Sudan. Unfortunately FGM is not criminalised in Sudan. I visited the Saleema organization (an FGM Initiative) and got some leaflets in Arabic. When I told them that I was from London I was cautioned that I have to work hard in London, USA and Canada because families are coming from there to do FGM in Sudan. During the trip I had conversations with a taxi driver who drove me to the Saleema Office. On the way we talked about Saleema and FGM and he said next week he was planning to have his two daughters aged 7 and 8 years to undergo FGM. I was shocked and informed him about what I had learnt from FORWARD. I asked to visit his wife to give her advice and he agreed to take me to meet her where I had the chance to talk to his wife and family about what the harm she will cause to her lovely daughters. She cried and promised me she will no longer do the FGM. I asked her to take a photo with me but she refused. I hope we work hard against this FGM."

|

|

|

|

|

|

Striking the right balance between protection, prosecution and prevention |

|

||||||

|

|

Both in Africa and Europe, criminal laws are one of the main strategies to abandon female genital mutilation. The perceived advantages of using the law to curb the practice are many. Laws create an enabling environment for interventions or to provide services, offer legal protection for women and help in discouraging excisors and families to continue with the practice. It also supports professionals in rejecting any requests to perform FGM. However, the implementation of criminal laws remains limited both in Africa and in Europe. Evidence has shown that two main issues with the implementation of the laws are apparent in Europe. First of all, reporting of cases remains problematic. Among front line workers, the lack of knowledge on FGM and how to deal with it, are one of the main reasons for not reporting FGM. Professionals are also reluctant to report to judicial authorities, or do not have knowledge or mechanisms at hand to refer girls at risk or women with FGM. In addition, communities themselves are equally not keen on reporting cases of FGM. Secondly, finding sufficient evidence to bring a case to court is difficult, for example when a girl has undergone FGM in countries of origin, or when non-family members have performed FGM. Moreover, the onus of proof on girls who have undergone FGM when they need to testify against parents and/or families in court hampers applying the law. Els Leye during the REPLACE 2 Conference in London. Studies have also demonstrated that cultural relativism influences the views and actions of some professionals, leading to not acting in cases of risk or provision of care. Personal and cultural prejudices among actors in the judicial system and child protection sector further obstruct addressing FGM as a criminal offence. In addition, the current financial crisis and prevailing discourse in Europe on migration, is not favourable for prevention and protection actions, that require a long-term commitment from policy makers and donors. In the EU, very few policies and training for professionals are available on prosecuting FGM and protecting girls at risk of FGM. Child protection policies have been developed in some EU countries, and include procedures to assess risk and outline how to respond to potential cases of risk, in accordance with national laws. Such policies and risk assessment tools are highly necessary to better protect those at risk of FGM. The prevention of FGM in Europe is primary done by civil society organizations. The bulk of their activities focus on raising awareness of FGM among the general public, communities and professionals, providing training for professionals and doing advocacy. A number of challenges regarding prevention have been identified, but one of the most important issues is that the support and resources for civil society organization is limited and mostly short term, which hampers their efforts considerably to focus on long-term behaviour change interventions. In conclusion, the needs to deal with FGM in Europe are huge and should be prioritized. Prevention should primarily focus on behaviour change strategies, and in the field of protection and prosecution, the focus should be on capacity building of professionals rather than on repressive measures that focus on the perpetrators. Criminal laws set the legal standard but prevention and protection are the strategies than can really foster behaviour change. Source: this article is based on the key note presentation by prof Dr Els Leye, at the REPLACE 2 Conference in April 2014 in London, and findings from the study "Female genital mutilation in the European Union and Croatia", EIGE 2013.

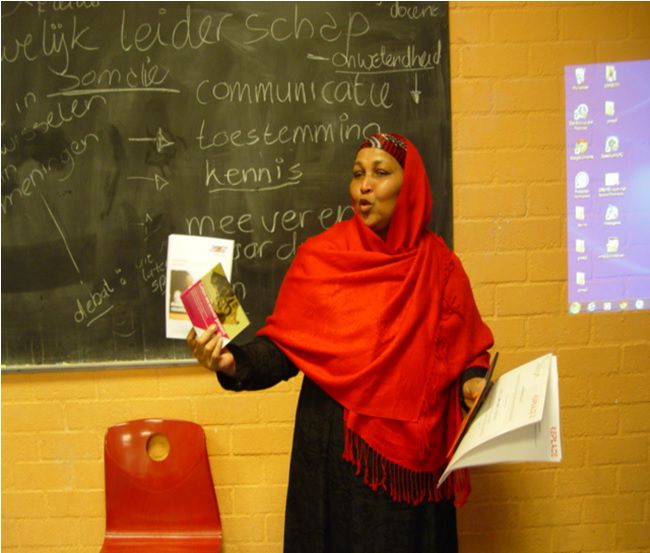

Training on women health, FGM and leadership in The Netherlands Spread the word! REPLACE 2 is followed by more than 500 stakeholders! Help us disseminate our work by spreading the word through our website and social network pages: https://twitter.com/replacefgm2 If you need any advice from the REPLACE 2 team please write to: |

|

|

|||||

|

(REPLACE 2 Project Number:

JUST/2011-2012/DAP/AG) |

||||||||